Why is media coverage of the security sector crucial?

Guest(s): Jacqueline Dalton, Head of editorial content at Fondation Hirondelle

In this episode, we speak to Jacqueline Dalton, Head of editorial content at Fondation Hirondelle. For over 30 years, this non-profit organisation has been building and supporting local media and journalists in fragile contexts to ensure that people facing crises have access to reliable, local, independent information.

Featured Quotes

Key takeaways

- Journalism provides accurate timely and relevant information so we can all make sense of the world.

- The media are acting as a watchdog for security actors, tracking abuses, human rights violations, dysfunction.

- The absence of information leads to a fatal breeding ground for disinformation.

- Wherever there is conflict there is a deluge of false information.

Maritie Gaidon

Welcome to Shaping Security, the podcast where we put security governance at the heart of the conversation and update you on today's security challenges. Today with me is Jackie Dalton, the Head of Editorial Content at Fondation Hirondelle. For this first episode of the series, we'll talk about media.

Why media in a podcast about security sector governance? Well, a journalist covering security institutions and states will be dealing with very sensitive issues that threaten the roots of democracy, such as corruption, lack of oversight, disinformation in times of crisis, and so on. It's all about the balance of power.

And this is why it's so important to talk about it. And fortunately, Jackie is with us. She will help you understand what it means to be a journalist covering the security sector.

Hi, Jackie. Thank you for being here.

Jackie Dalton

Hi, thank you very much for the invitation.

Maritie Gaidon

I'm really excited you're our first guest. So thank you again. Pleasure.

Before we deep dive into the question, a quick catch up for listeners on what is Fondation Hirondelle. So Hirondelle supports local media and journalists in conflicts and fragile contexts. For example, the Sahel, Ukraine, and they have done this for over 30 years.

So humanitarian crisis, disinformation, coverage during democratic processes like elections. They are experts and I'm super glad Jackie is here.

Jackie Dalton

Thank you.

Maritie Gaidon

So let's start with the first question. Overall, people know that it's important that journalists share information with the public, especially on topics considered as very secretive, like in the security sector, for example, the use of force, as I mentioned before, corruption. But if you ask people why journalists are so important, you realise it's super hard for people to explain why this oversight is key for their rights.

So can you explain what is the role of the media in covering issues related to the security sector, why their job is crucial?

Jackie Dalton

So at its core, journalism does a number of things which are equally relevant, I would say, to the security sector. So, of course, first of all, it's just about keeping people informed. It's really difficult to make good choices in your life if you don't understand the basic facts of what is happening around you and who is doing what, whether it's rebel troops advancing towards your village, whether it's the stock market tumbling that's hitting your savings, what are the signs of the Mpox virus and what do I do if I have them?

Who are these people standing for elections? So journalism is doing that basic fundamental and often I would say taken for granted job, which is providing accurate, timely, relevant information so that we can all make sense of the world. And when it comes to the security sector, that means things like explaining to the public what these institutions are, how they're led, how they function, what they're doing right now.

So the who, what, where, when, why's. And often if people don't have that basic level of information, I think they're more likely to get suspicious and mistrustful, which in turn will make it harder for those in the security sector to do their job. So I think that's number one is keeping people informed.

And of course, conversely, the security sector also draws on the media to understand what's happening so that they can make informed decisions. I think the media also has this kind of bridging role between citizens and authorities by helping to relay public concerns, explain security policies, and providing a platform for public discourse and to encourage proper reflection on issues. To give you an example, my colleagues in the Democratic Republic of Congo have recently done a couple of programmes about 'popular justice' in DRC, which is illegal.

Essentially, it's people taking justice into their own hands. And there've been a lot of cases of people who are suspected of stealing something or committing some other crime who get simply burned to death or beaten without going through the proper processes. And the advantage of having a space in the media where you can explore these issues is that you can begin to understand what's happening and what needs to be done about it.

Obviously, in this example, there are multiple issues around popular justice and why it happens. But one of the main things that came forward in these discussions was just about a trust issue. People don't trust, in some cases, in the country's existing processes and systems.

So they end up taking things into their own hands. And I think it was really important to be able to give space for people to air those concerns and hear reactions to them. Also, of course, one of the major roles of journalism is about holding power to account.

So there are the big examples: Watergate, the Panama Papers... Journalism shining a light where people in power don't want you looking. And on a daily basis, the media acting as watchdogs for security actors, tracking abuses, human rights violations, dysfunctions. And this happens on a daily basis around the world.

Earlier this week, I was watching one of my favourite examples of this. It was a piece done by BBC Africa Eye about seven years ago. And you can find it on YouTube.

It's called 'Anatomy of a Killing'. And it's a video that began to circulate on social media showing two women and two children being led away at gunpoint by a group of Cameroonian soldiers. And they were forced to the ground and shot 22 times.

The government of Cameroon initially dismissed the video as fake. But BBC Africa Eye did a really thorough analysis of the footage and proved exactly where this incident happened, when it happened, and even identified who was responsible for the killings. And that prompted a massive international reaction.

The guys in question ended up in prison. The US shortly afterwards reduced security aid over concerns of human rights violations, so demanded higher standards. And I think what was so extraordinary about this, apart from the international impact, was the way the work was explained to the public.

Not just, this is what happened. It's, this is how we know what happened. Here are the photos of the weapons.

And we can tell that they're from such and such a location. The shadows of the soldiers tell us information about where and when. The uniforms.

So I think it was with a level of transparency and detail that, you know, no arguments could be had about what happened. And it led to, I think, a whole new wave of enthusiasm for investigative open source journalism. So that's, you know, that's quite a big example.

But I think just the fact of knowing that someone is watching you, that you're under scrutiny, also plays a preventative role. So it's not just about exposing things when they happen. It's about them being less likely to happen, because you know you might get into trouble for them.

And giving a voice to the voiceless. So, you know, those women and those two kids, they wouldn't have had their story properly told if the media hadn't been there to show the truth about what happened.

Maritie Gaidon

Yeah, definitely. This is such a good example. And I really thank you for having given this.

And this is also such a good overview, you know, of like, the work of journalists. You have given three big points that really help us to visualise everything. And actually, your example leads me to another question.

This is on your website. There is a quote that states, Journalism makes it possible to distinguish between a fact and a lie, particularly in fragile situations where disinformation is often the first weapon to be deployed, you know. So the use of the word 'weapon' is very interesting.

And you have just also used it, you know, because it's a word associated with violence. And here, disinformation. So how is this specifically impacting journalist reporting on the security sector?

Jackie Dalton

In terms of disinformation?

Maritie Gaidon

Yeah.

Jackie Dalton

So as you say, I mean, it's a tool. It's a weapon of war, I would say.

And I think warring parties will often use fake news to justify their actions, to influence populations, to discredit journalists. That's been the case for a long time. I think it's being made easier now with the help of artificial intelligence, which is able to share this information on a new level, a new scale and with even more convincing content than before.

I mean, I think wherever there's conflict, there is a deluge of false information. So a couple of examples of, you know, stories that different teams have been debunking recently. So Radio Nikkei Luka, our media base in Central African Republic, has recently debunked claims by some news media and on social media that the army in Central African Republic had said that Ukraine was working with France to plan a drone attack on Central African Republic.

In DRC, you can imagine the amount of false information flying around right now in relation to the conflicts. One of the latest ones was about involvement of EU or Belgian forces in the fighting in Eastern Congo. And of course, there's been an absolute flood of disinformation around Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

And I think all this really impacts on public trust. I think when the climate gets saturated with false information, audiences struggle to trust the media. And it becomes difficult for the media to fulfil their watchdog role as well.

And I think one thing that's really important is that we can't, I mean, there's so much false information, we can't hope to correct and debunk everything. That's not the solution. It's maybe part of the solution.

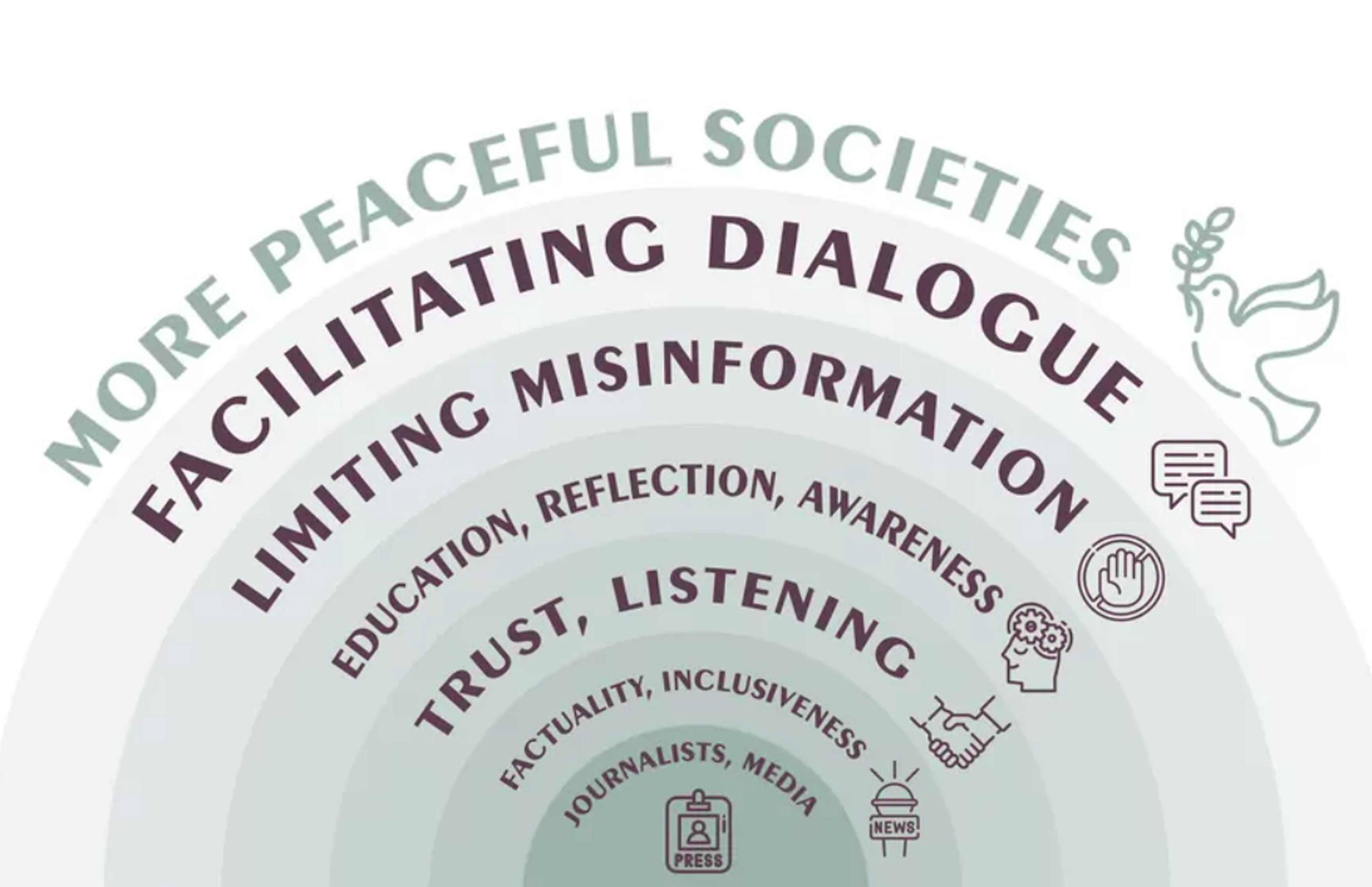

But I would say that your best approach is to start by providing in the first place, accurate, reliable information about what's happening to fill those information gaps. As human beings, we don't like not knowing what's happening. And sometimes we would rather believe a lie than just accept that we don't know.

So an absence of information leads to a fertile breeding ground for disinformation. And trust is the other factor in this. If people don't trust sources, then it's going to be harder to convince them of the truth.

This is true for media. It's also true though for different institutions and security institutions. It's about communicating proactively in the first place to avoid these kinds of information gaps and to build trust.

And not just about public relations, I also mean about transparency, about proximity. Trust is also built by listening. So it's not just about giving out information.

It's about listening to people's concerns, showing you're listening, responding to them. If you do all this work, it's going to be much more easy to avoid the spread of disinformation. And when you do debunk it, you're much more likely to be trusted by people.

Maritie Gaidon

That's such a good transition because actually DCAF works with journalists and the police, and we have also found that one of the key elements to better monitoring and reporting is trust and also understanding between the police and the media because each can then better understand the challenges they face, the restriction, the rules they have to follow to do their job. So my question would be, what do you think is the most effective way to build this trust between security institutions and the journalists? Because you mentioned providing accurate information, but it's more with the public, but between really the security institutions and journalists, what are the most important things to create this trust?

Jackie Dalton

It's interesting because in many ways, the values of journalists and those in the security sector, in theory at least, are aligned because it's in both cases about working in the public interest. It's about impartiality, accountability, transparency, serving the common good. So in a sense, public interest media, and I should perhaps also add the caveat that not all media equal, not all media have the same goals.

Some are not working independently, but in terms of public interest media, we're completely aligned in fact with what should be the goals of the security sector. So I think even starting on that basis is helpful. I think there is automatically mistrust between the two sides.

I think those in the security world probably feel like they're being hunted. They're worried about misrepresentation of their work or sensationalism, which also as media, we have to acknowledge sometimes happens. So it's our duty as journalists to be accurate and fair in the representation of what's happening.

And I think in the real world, not all security institutions are equal either. They're not always working in the interest of the public and the journalists are finding themselves faced with institutions and systems that are very powerful by nature, secretive and sometimes dangerous. So I think there's work to be done.

There's work to be done on even bringing them together. I've worked quite a lot in the humanitarian world as well, bridging the divide between journalists and humanitarian actors where there's the same level of kind of, well, perhaps not the same level, but there's a certain degree of fear and mistrust. I've done loads of workshops and trainings, bringing them together to just talk about these issues and discuss like, what are the sticking points?

How can we ensure that in order to both achieve our different goals, we work together more effectively for the public because we're there to serve them? So I think having open spaces for honest conversations is also really important and helpful. And I would also, you know, be, there are some media that you can trust more than others, put it like that.

And I think it's worth security institutions investing their time in identifying who those are and building with relationships with them over the long term.

Maritie Gaidon

That's interesting, this notion of there are also some media that you can trust more than other and some security institutions also that are like, you know, sharing more than others.

Jackie Dalton

Right, exactly. And I think, you know, that's also one of the challenges in the places where we work. So as you mentioned, we, you know, we tend to work in fragile and conflict settings.

You know, things are really, really difficult in that regard. I mean, if we zoom out a little bit, I think journalism, or at least good independent public interest journalism, is under huge pressure globally. There's financial pressure because generating income is getting harder and harder.

There's competition from new platforms, new voices that are sapping up people's attention and, you know, why watch the news when you can watch Netflix? And in, you know, in the countries where we work, a lot of journalists don't get paid enough to be able to eat basically. So that means that they'll end up going to press conferences where at the end they'll receive an envelope of cash.

And obviously accompanied with that envelope is the subtext of you're going to say nice things about us. So that straightaway compromises independence, accuracy, impartiality, which are three of the fundamental principles of good journalism. I mean, the media we work with have the luxury of not being able to accept those envelopes, and it's a very serious offence if they do.

But the reality of the financial situation is that, you know, people need to eat and many journalists will end up doing that. So you get information which is not necessarily fair and balanced about what's happening. And I think also there are strategic, deliberate attempts to disable and to silence the media.

This is not new at all. I mean, it's been happening forever. But I would say in a lot of the countries where we work, this is getting worse.

This manifests itself in different ways. On a very simple level, it's about discrediting journalists and media organisations, the fake news media. So to take, you know, a recent example, which we'll all be familiar with, is the Signal Group chats about the plans for US strikes in Yemen, to which a journalist was added when he shouldn't have been.

And when he revealed this, the response from the White House was to blame the journalist and try to discredit him. So, you know, 'Jeffrey Goldberg is a total sleazebag who tells lies', 'the Atlantic is a failed magazine', etc, etc. So shoot the messenger, undermine the media, and distract attention from the real issue that's under question.

At another level, I think there's issues of restricted access to information. So it's simply about not providing the information that normally should be made available. I'm thinking of Democratic Republic of Congo right now, where, you know, reporters are trying to cover the military operations and the armed groups.

And it's often, you know, just a wall of silence about what's happening. You know, there are places where we'll get regular government press releases about huge successes fighting terrorists, but it's very hard to dig beneath that and really get a good picture of what's happening. You know, those are kind of, I would say the more benign things that are going on, but on a much more explicit level, journalists are facing more and more threats and intimidation in the countries where we work if they raise uncomfortable questions.

So either by government or by non-state actors, you know, journalists are disappearing, finding themselves in prison, finding themselves being beaten.

Maritie Gaidon

Yeah.

Jackie Dalton

It's really quite horrific what's happening.

Maritie Gaidon

That's actually something I want to discuss with you because we'll look at some numbers and the International Federation of Journalists say that 122 media professionals have been killed in 2024. And UNESCO report that more and more journalists are detained, subject to online attack. That is new, but also surveillance operation.

It is also AI and all of this. So they are facing real threat, as you have just said, you know. Can you give us one concrete example in the work of Hirondelle where you have faced one of these challenges, but also most importantly, how journalists have tried to put in place solutions to overcome it?

Jackie Dalton

Yeah. So, I mean, I think it's happening in the countries where we work all the time. And, you know, the reality is that in, you know, the Sahel is quite a good example that there are countries there where we're really struggling to be able to have proper debate and discussion and provide information about the reality of what's happening in the country.

Because so far, this has not happened directly to any of our journalists, but in other media, there are journalists who, you know, who've disappeared overnight. And it's really hard because these are journalists, are local journalists working in the country, which is very different from being an international broadcaster working from outside where you can, you know, get away with a lot more. Although a lot of the international broadcasters are being blocked right now in the Sahel.

So they've got this real level of vulnerability because, well, everyone knows where they live kind of thing. And so it's really tricky. I think one of the number one rules about protecting yourself in this situation is about sticking to the basics of good journalism.

So being irreproachable in terms of checking your facts, respect for balance, diverse voices, impartiality, because the moment you do something that's slightly off or that leaves scope for questions, then that will be used against you. So that's kind of the number one answer to everything is do good journalism. I would say we also rely quite heavily on civil society.

To give you an example of something that happened a couple of years ago in the Sahel region, there was a killing of a large number of civilians and the information was coming out that it was government forces with foreign help who were involved in those killings. And our journalists knew that this was happening. They were getting information from the local communities, but they could not put it on air or they couldn't be the first ones to put it on air because it's just too much of a risk to do that.

But what happened is that it got denounced internationally. You know, groups such as Human Rights Watch play a really important role in that. It gets international media coverage and then the government will react to that.

And once the government has reacted, we're in a better position to be able to start treating the story and talk about it happening because we're not breaking it anymore, but we're still managing to cover it. So in that sense, we really need more than ever the voices of different organisations of civil society and human rights, locally and internationally, to be able to denounce some of the things that are happening so that we can treat them as well. We're very careful with our language.

In journalism, you always should be, but I think in conflict settings, it becomes even more significant. And in journalism, there's one word which is quite complicated, which is the T word, terrorist. In our media, we don't have a ban on using that word, but the message is think very carefully before you use it because it's often being used by different actors to justify certain actions and its attempt to kind of stigmatise whole groups of people without necessarily looking into the nuances of who they are, what they're doing, what they're fighting for.

As the expression goes, one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter. So it's about nuance and not oversimplifying things and feeding into what is sometimes, not always, but sometimes attempts of propaganda. But there's recently been, we recently had a demand to use the word terrorist.

Consistently, whenever we talk about non-state armed actors, they must be described as terrorists and UN agencies and humanitarian agencies have in some cases been asked to do the same thing. And that's obviously very problematic and it's not for anyone else to tell journalists the language that they use. But yeah, it's just details like that, which are not insignificant and they're creating all kinds of challenges.

Maritie Gaidon

Wow, that's really super interesting. Thank you. And actually for me, that was my last question.

So I really want to thank you, Jackie, for being here on the podcast. I have to say that in only four questions, I'm impressed by how many details and information you have already shared with our listeners. Personally, I think I will remember the three words that you have given, key for journalism, impartiality, transparency and accountability.

And also you mentioned several times this idea of building bridges between citizens and authorities, between journalists and police. I think it was brilliant. So really, thank you, Jackie.

Jackie Dalton

Pleasure. And yeah, I think those three keywords that you highlighted are so important. They're so important to the media and they're so important for actors in the security world.

So yeah, I'm with you on that.

Maritie Gaidon

Thank you.

Jackie Dalton

Thank you very much.

Maritie Gaidon

Jackie mentioned 'Anatomy of a Killing'. I have watched it since Jackie and I talked. I can definitely confirm that.

It's a must watch. And now I've got two other resources for you to delve deeper into today's topic. This is just a short selection.

You will find much more on the podcast page on our DCAF website. The first resource I want to share is a TED talk by Alison Killing, How Data-Driven Journalism Eliminates Patterns of Injustice. She uses the example of detention camps in China to explain how journalists have successfully used open-source data to reveal the truth about these camps.

The talk is only 12 minutes long, but it's well worth your time. The second resource is a toolkit for media professionals. It has been created by journalists for journalists.

It focusses on their needs when reporting on the security sector, especially in conflict-affected and transitional contexts. The good news is that it's already available in five languages, English, Arabic, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. The links are in the description of the episode and additional resources on media and security governance can be found on DCAF.ch. Thank you for listening to Shaping Security, the podcast where we put security governance at the heart of the conversation and update you on today's security challenges. If you enjoyed the podcast and would like to support us, please share it with a friend or leave us a review on your preferred podcast platform. You can find out more about DCAF on our website and our social media channels. We also have a monthly newsletter that shares our latest resources.

Don't miss the next episode of Shaping Security.